There’s a disclaimer at the beginning of Nell Stevens’s latest book, confessing to having “changed names, scenes, details, motivations and personalities” in both the personal and the historical sources for this partly autobiographical romance, which is also a love letter to Elizabeth Gaskell. The Victorian novelist and her contemporaries are “not always faithfully quoted”, Stevens warns, but neither is the author (or, rather, her avatar, Nell), who is in the famously difficult position of telling a story. Truth is slippery, biography sort of pointless, and autobiography the worst of all. Let’s just call the whole lot fiction right from the start.

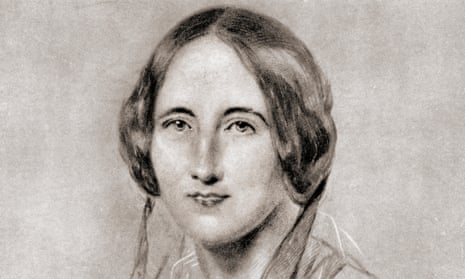

Readers of Bleaker House, Stevens’s 2017 dashing debut, will recognise the tone and the ingenuity of this, and imagine they recognise the heroine too, at a different stage of her young adult life. Bleaker House was a fictionalised memoir about “Nell” going to the Falkland Islands to write a novel; Mrs Gaskell & Me is about “Nell”, a love-sick postgraduate, struggling to write a thesis about Gaskell. She weaves her story of thwarted scholarship and thwarted love (for an unresponsive friend called Max) through that of Gaskell leaving Manchester for Rome in 1857, just before the publication of her controversial Life of Charlotte Brontë. Gaskell was fleeing possible critical backlash against her book and successfully forgot her troubles (for a while) among the artists and writers who had gathered around the American sculptor William Wetmore Story – including Harriet Hosmer, the Brownings, Harriet Beecher Stowe and Charles Eliot Norton. Rome remained Gaskell’s ideal, and those months of freedom and excitement “the tip-top point of our lives”.

Licensed by Gaskell’s ecstatic memories, Stevens imagines she fell in love there, too, with the charming young Norton, and depicts Gaskell’s first sighting of him from a Roman balcony at carnival time like a slo-mo scene from a movie: “You had watched him disappear beneath you … and there had been a disconcertingly long wait for him to reappear”. But back in the present time, Nell is spending long, fruitless days in the library, entering online competitions and volunteering for medical studies in order to visit her in every way distant boyfriend. When she achieves her goal, the disappointment is overwhelming and, in some brilliantly painful vignettes, Nell gets mawkish over stubble in the sink, or has to snatch “a long gulp of a stare” at Max while his back is turned. “Desire is private and incomprehensible, confined to specific bodies in specific times”, she decides; it is perhaps easier to imagine Gaskell’s love for Norton than account for, or even remember, her own experiences.

In Bleaker House there was a great deal of play on the difficulty of finding something to write about, and a wonderfully surreal scene in which the narrator, filming the pilot of a reality show called Any Idiot Can Write a Book, has to keep saying that what’s wrong with her novel is that “nothing happens”. Well, quite a bit happens in this book, and even when not much is happening, the collage structure, chopping from Mrs G to Nell and then (less successfully) to other members of the Rome circle, gives an impression of constant movement.

But I found the dramatic events, such as a tornado in Austin, a seance, a medical emergency and an unconventional honeymoon in India, considerably less arresting than Stevens’s claustrophic scenes in bedsits and restaurants, seminars and readings. She has an analytical eye and a wonderful taste for absurdity. The graduate student seminar in which Nell has to respond to a paper on Pig-Human Relations in Jude the Obscure is one of the funniest things I’ve read in ages, probably because it doesn’t struggle to satirise academic fashions and obsessions, but simply opens them to view. Just as funny is her depiction of the silence in a writers’ workshop following a psychotic rant called “The Maiden or the Mistress”, broken by one hesitant voice: “I thought the rhymes were really good”.

The poet in that scene complains, of course, that he is writing from personal experience, and so is beyond criticism. Stevens’s disclaimer about truth and lies reverses that neatly, and leaves us to deal with the liberties she has taken (the ramping-up of Gaskell’s feelings for Norton, for instance, or the insistent slighting of her husband and his “dull, dull, dull” sermons). They’d be hard to swallow if the book wasn’t also afloat with admiration and affection for its subject. “I have never encountered a writer who could fill a page so entirely with herself,” Nell says of Gaskell’s wonderful letters.

Stevens gives three different endings for her own character’s story and one different one for her heroine, who is spared the sudden death she suffered, aged 55, at the house in Hampshire she had bought without her husband’s knowledge, and is instead allowed to travel to America and be met on the dock by a smiling Norton. All cake is to be both had and eaten in this celebratory, charming, thoroughly fictional book.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion